Since the 1990s, conditional cash transfer (CCT) has occupied a prominent place in the public agenda for social protection, poverty alleviation and access to food in Brazil. These programmes are targeted at families that live under adverse conditions and whose nutritional status is impacted by multiple constraints such as difficulty in accessing and consuming an adequate quantity and quality of food(Reference Lagarde, Haines and Palmer1) or living with some degree of food insecurity, as highlighted by Burlandy and Salles-Costa(Reference Burlandy and Salles-Costa2). The Brazilian Federal Government invested in CCT through a programme called the Bolsa Família Programme (Programa Bolsa Família).

Based on the assumption that food security is a human right and a public good that is realised through universal public policies(3), one of the objectives proposed by the CCT was to fight hunger and promote food security. This objective can be achieved by increasing family income for food purchasing or by altering the challenging conditions encountered by the participating families.

CCT benefits more than 11 million families with children ranging in age from 0 to 17 years and with a monthly per capita income ≤$US 60·91. Families with a monthly income ≤$US 30·50 can participate in the programme regardless of the presence of children or adolescents. Families received a monthly income from the CCT ranging from $US 10·15 to $US 92·39(4, 5).

Studies of the impact of CCT programmes implemented in Nicaragua, Colombia, México and Africa on food consumption, health and nutrition have shown that the resources received by households are primarily used to purchase food(Reference Attanasio and Mesnard6–Reference Harvey and Savage8). In Brazil, an evaluation of the Bolsa Alimentação Programme (Programa Bolsa Alimentação – a former CCT programme intended only for low-income families with school-age children) indicated that dietary diversity and family food expenditures increased, with families purchasing more food specifically for children(9). Furthermore, with respect to improvements in food consumption, Morris et al. provided strong evidence that the Bolsa Alimentação Programme contributed to the nutritional recovery of children with severe deficits in weight-for-height and height-for-age(Reference Morris, Olinto and Flores10).

A survey was conducted among a population-based sample of Brazilian families that had benefited from the CCT in 2007 to evaluate the effects of the CCT on the food insecurity of families(11). Data on self-reported food consumption based on this survey were used in the present study to analyse changes and predictors of change in self-reported food intake among Brazilian families that benefitted from the CCT.

Methods

The study included a population-based sample of 5000 households selected from the March 2007 registry of the CCT, provided by the Senarc/Ministry of Social Development. The sample was selected in two stages. In the first stage, fifty municipalities in each region were selected with a replacement and probability that was proportional to the number of families that received benefits. In the second stage, twenty subjects were selected from each municipality with equal probability. Because the sample was based on information from an administrative registry, a reserve sample was selected to replace cases of non-response due to incomplete or out-dated addresses, refusal to participate, temporary absence of a programme participant or other reasons for non-participation. Refusal to participate was minimal, but 51 % of the final sample was obtained from the reserve sample due to incomplete addresses.

The study was developed by the Brazilian Institute of Social and Economic Analyses (IBASE), proposed by the Reference Centre on Food Security and Nutrition (CERESAN) and the Network Development and Education Society (NETS), and co-coordinated by the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the Federal Fluminense University.

Instrument preparation for data collection and quality control

The questionnaire was developed using questions from previous qualitative research and from questions used in other studies. The pilot study was used to train five regional supervisors. Training was performed with a team of researchers using simulated interviews of CCT participants who were not included in the final sample. The selection and training of interviewers was conducted by the private company responsible for collecting the data (Vox Populi). Data collection was performed between 13 September and 26 October 2007 under the supervision of consultants and researchers from IBASE, who randomly selected municipalities in which to monitor the fieldwork. The interviews were conducted in person with the CCT benefit holder, who was typically the individual responsible for feeding the family. In most cases (93·6 % of sample), this provider was a woman.

Socio-economic and demographic characteristics

Variables included: (i) the country region of residence (mid-west, north-east, north, south-east or south); (ii) family composition (with or without the presence of a partner and children); (iii) the gender and race of the benefit holder (self-reported race as white, black/mulatto or Asian/Indigenous people, in accordance with the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics(12)); (iv) years of education of the benefit holder (illiterate, ≤8 years, 9–11 years or ≥12 years); (v) employment of the benefit holder (with or without salary during the month preceding the survey); (vi) number of residents (four or fewer, five to eight, or nine or more people living in the house); (vii) housing type (house, apartment or room/shack); (viii) water supply (public net or other forms); (ix) garbage collection (public net or other forms); and (x) duration of participation in the CCT (≤12 months, 13–24 months or ≥25 months).

Perceptions of food consumption

Possible changes in self-reported food intake after participation in CCT were evaluated using the following question: ‘After you began receiving CCT benefits, consumption of _______ among all of the residents of your residence: (i) increased, (ii) decreased or (iii) has not changed’. The food list comprised twenty-nine foods organised into sixteen groups as follows: Cereals, including rice, corn flour (or corn meal or popcorn), rice flour (maize starch and others), bread (or wheat flour), cakes, cornbread, tapioca, corn and pasta (n 4986); Cookies, including biscuits or crackers (n 4941); Milk and dairy, including cheese, yoghurt, curd and chocolate prepared with milk (n 4996); Eggs (n 4997); Fruit and natural fruit juices (n 4,997); Vegetables (n 4992); Beans (n 4994); Meat, including red meat, chicken, fish, pork, lamb, goat meat and game meat (n 4994); Fats, including margarine, butter and oils (n 4994); Processed foods, including sausage, alcoholic beverages, canned products and ready-to-eat products (e.g. industrialised juices, instant noodles; n 931); Fried foods, including food prepared by immersion in oil (n 709); Roots and tubers, including cassava, potatoes, sweet potatoes and yams (n 4998); Sugar, including sugar, honey and cane molasses (n 4904); Sweets, including sweets, jams, ice cream, gelatine, candies and chocolates (n 1828); Soft drinks (n 2798); and Coffee, including tea and mate (n 4863). The number of answers for each food group varied due to lack of consumption of the item both before and after inclusion in the programme.

Food insecurity

The present study used the Brazilian Food Insecurity Scale (Escala Brasileira de Segurança Alimentar – EBIA), which was adapted and validated for Brazil by Pérez-Escamilla et al.(Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Segall-Corrêa and Kurdian Maranha13). The internal validity of EBIA is high (Cronbach’s α of 0·91). The EBIA has fifteen ‘yes/no’ questions and measures the concerns of each subject regarding food shortage or total food absence over the prior 3-month period. Among the fifteen questions, seven are related to family members who are less than 18 years of age. Families with children answered all fifteen questions, but families without children answered only eight questions. Depending on the family composition (with or without children) the cut-off to define food insecurity degree is established as suggested by Marín-León et al.(Reference Marín-León, Segal-Corrêa and Panigassi14). Each affirmative answer was assigned one point and the results were classified according to different degrees of food insecurity: (i) food security; (ii) mild food insecurity (mild FI), fear of suffering food insecurity in the near future; (iii) moderate food insecurity (moderate FI), restriction of the quantity of food for the family; and (iv) severe food insecurity (severe FI), hunger among adults and/or children in the family.

Dependence on conditional cash transfer benefit

Total family income was estimated as the sum of all of the family income during the month preceding the survey, considering income from work (including the sale of agricultural products or informal employment), pension or CCT pension, Programme for Eradication of Child Labour benefits, other government CCT programmes (not including financing or lines of credit) and other sources of income. Based on this value, the percentage of income that was dependent on CCT benefits was estimated by calculating the ratio between the income earned exclusively from CCT benefits and the total income. Income was expressed in $US and the dependence on CCT benefits was categorised by quartiles as follows: first quartile, ≤8·4 %; second quartile, 8·5–16·2 %; third quartile, 16·3–27·3 %; fourth quartile, ≥27·4 %.

Data analysis

The prevalence of food insecurity was estimated according to the EBIA classification. The χ 2 test was used for comparisons across categories and P < 0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Using Poisson regression models, the relative risk was measured based on prevalence ratios (PR) and their confidence intervals (95 % CI) were estimated to assess the strength of the associations of independent variables (food insecurity, country region of residence, dependence on CCT benefit, duration of participation in CCT) in relation to changes in the consumption of each food group reported by the households. An absence of change in consumption in each group was used as the reference category in the models. Because there was no observed decrease in any food group, we decided to exclude this item.

All analyses were based on the weighted prevalence and incorporated the cluster-sampling design using the STATA statistical software package version 11·0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

The Research Ethics Committee of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation approved the project in 2007. At the time of the interview, a consent form was submitted in which the interviewee agreed to participate in the study following clarification of the study procedures, assurance of confidentiality of the information provided and confirmation of the right to refuse participation.

Results

Families classified as having food security were less dependent on CCT benefits. Residents of the north-east region depended more on CCT benefits than did residents from other regions. In contrast, the populations of the south-east and mid-west were generally in the lowest quartile of dependence. The populations that lacked a water supply and garbage collection were in the higher quartiles of dependence. An equivalent finding was observed when the benefit holder did not receive a salary or possessed less than eight years of education. Moreover, smaller families (four people or fewer) demonstrated a greater dependence on CCT benefits (Table 1).

Table 1 Socio-economic and demographic characteristics by dependence among participant families that benefitted from the conditional cash transfer (CCT) programme, Programa Bolsa Família, in Brazil, 2007

Significant association between variable and quartile of CCT dependence (χ 2 test): **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

†Weighted values.

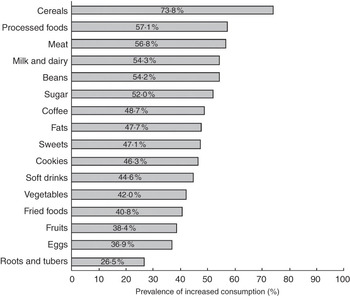

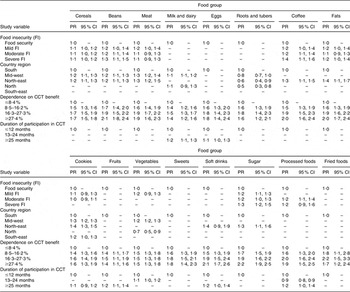

Families reported an increased consumption of all food groups analysed. More than 50 % of the study population reported an increased consumption of cereals, processed foods, meat, milk and dairy, beans and sugar (Fig. 1). The Poisson univariate analysis revealed that a severe level of food insecurity was associated with a greater prevalence of families that had increased their consumption of coffee, sugar, beans and fats (Table 2). Participants living in the north-east region demonstrated a greater increase in the consumption of all food groups, especially fats, sugar and coffee (Table 2). Dependence on CCT benefits for income was strongly related to this increased consumption; a statistically significant increase in the prevalence ratio was observed when the highest and lowest intakes were compared for sugar, coffee, fats, beans and soft drinks. The participation duration had no effect on changes in food intake; however, most participants demonstrated almost the same duration of participation in the programme. Following the multivariate analysis, dependence on CCT benefits remained associated with increased consumption of all food groups (Table 3).

Fig. 1 Prevalence of the increased consumption of specific food groups in participant families of the conditional cash transfer programme, Programa Bolsa Família, in Brazil, 2007

Table 2 Prevalence ratio (PR) and respective confidence intervals (95 % CI) for the self-reported increase in food consumption estimated by a univariate Poisson regression model according to the study variables among participant families that benefitted from the conditional cash transfer (CCT) programme, Programa Bolsa Família, in Brazil, 2007

Table 3 Prevalence ratio (PR) and respective confidence intervals (95 % CI) for the self-reported increase in food consumption estimated by a multivariate Poisson regression model according to the study variables among participant families that benefitted from the conditional cash transfer (CCT) programme, Programa Bolsa Família, in Brazil, 2007

Discussion

Important changes in food intake were reported by the participants in the CCT, but causal inferences could not be drawn from these analyses because a control group would be necessary to determine whether the observed changes were due to CCT benefits. The use of a control group however would be unethical.

The overall prevalence of food insecurity in the present study was 89 %, compared with 37·5 % in the National Survey of Demographic and Child and Women’s Health (PNDS/2006) and 34·8 % in the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD/2004)(15, 16). This difference suggests that CCT was successful in targeting populations at risk for food insecurity. Overall, we observed a significant increase in the consumption of all food groups. Families that demonstrated the most severe food insecurity, residents in the north-east of the country and those for whom CCT benefits provided at least one-fifth of their total income showed the most evident changes in food consumption. Increases in fruit and vegetable consumption were smaller than were those for cereals (mainly rice), beans, meat and milk. Processed foods and high-density, energy-rich foods demonstrated the largest increase.

A low intake of fruits has been observed in nationwide Brazilian surveys. Although fruit intake increases with family income, the overall availability of fruits and vegetables is equivalent to 30 % of the WHO recommendation of 400 g/d(Reference Levy-Costa, Sichieri and Pontes Ndos17). Even in the highest fifth income quintile of the Brazilian population, the purchase of fruits and vegetables is below the recommended level(Reference Claro, Carmo and Machado18). This finding could be explained by the greater cost of these food groups compared with other food groups(Reference Claro, Carmo and Machado18).

Burlandy and Salles-Costa(Reference Burlandy and Salles-Costa2) emphasised that compared with other support programmes, the CCT programme expands food access by improving consumption and allows its users the freedom to decide how the benefits will be spent. Consequently, analysis of the impact of the programme helped researchers understand the logic used in decision making and the factors used by families to prioritise consumption decisions in the context of many needs, including non-food needs. It is noteworthy that food preferences not only follow a policy of strict financial determinism (the purchase of foods that meet nutritional needs), but also involve a number of other conditions such as convenience of preparation, time spent processing, taste and the symbolic, cultural and psychosocial aspects of food consumption(Reference Burlandy and Salles-Costa2). Energy cost has been identified as a major constraint in decisions regarding food, especially in the lower-income classes, because industrialised energy-dense foods are cheaper than fresh foods. Moreover, considering the socially constructed parameters surrounding flavour and taste, sweets and high-fat foods are more practical and appetising(Reference Drewnowski and Darmon19). As noted in the present study, the primary food selection criteria used by families with greater food insecurity and dependence on CCT benefits were energy density combined with taste and availability (e.g. processed foods and sugar). Similar results were observed by Adato and Roopnaraine(Reference Adato and Roopnaraine20) for the CCT programme in Nicaragua, the Red de Protecion Social, in which families reported having the means to buy basic foods in increased quantity and frequency with programme participation. The results showed that beans were purchased more frequently in areas with lower income, and meat was purchased more often in areas with higher housing costs.

Because families living with the most serious levels of food insecurity have the lowest incomes and greater food deprivation compared with other groups, a parallel can be drawn between the benefits families receive from CCT programmes in Nicaragua and Brazil. Among the Brazilian families enrolled in the CCT in 2007, the prevalence of increased bean consumption was inversely proportional to income. The same phenomenon was observed in Nicaragua, where higher increases in bean consumption were observed in areas with lower housing costs.

Families that participate in the CCT live in poverty (per capita monthly income of $US 30·51–60·91) or extreme poverty (per capita monthly income of less than $US 30·50), and the benefits received are relatively small (ranging from $US 10·15 to $US 92·39 at the time of the study)(4). Therefore, the higher cost of foods such as meat, fruits and vegetables, which comprise a basic diet, tends to be critical in determining the purchasing choices of the benefit holder. In the context of more expensive foods, low-income families demand more affordable alternatives. Such alternatives generally include foods such as cereals, which are of lower nutritional quality and are low in micronutrients(Reference Silva and Tavares21).

Despite the increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, focus groups held in different cities of Brazil revealed that families characterised these foods as ‘non-essential’ and that they even ‘restricted the children’(11): ‘… the basics of many of us here are sugar, coffee, flour and beans’. This statement was obtained from a focus group report in Salvaterra (Pará), Brazil(11).

The consumption of these foods was probably not greater for a number of reasons, including the small proportion of these families that engaged in food production for self-consumption and the low contribution of other forms of access to fruits and vegetables such as free markets, as outlined by Segall-Correa and Salles-Costa(Reference Segall-Correa and Salles-Costa22). However, the opposite phenomenon was observed in families that benefitted from the Mexican CCT programme PROGRESA, which is currently known as Oportunidades. After a year of participation, the families reported increase in energy intake from vegetables, fruits, meat and animal products(Reference Hoddinott and Skoufias23). Data from Familias en Acción, a CCT programme in Colombia, reported consumption patterns similar to those of the Mexican families, with the greatest observed increases in foods of animal origin and smaller increases in cereals and fats(Reference Attanasio and Mesnard6).

Most families that received CCT benefits (87·4 %) did so for more than 1 year, and the duration in the programme did not affect food intake. Despite the positive effects of CCT programmes on food consumption and improved health and nutrition(9), both the current analysis and the analysis of the Family Research Budget (Pesquisa de Orçamento Familiar – POF), conducted in Brazil in 1988, 1996 and 2002/2003, suggest an increased consumption of saturated and hydrogenated fats, a reduced consumption of nutrient-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables, and an increased consumption of fatty, salty and energy-dense foods with poor nutrient values(Reference Claro, Carmo and Machado18). Several studies have demonstrated an increasing risk of obesity among families that live in food insecurity as the consumption of such food groups rises(Reference Olson24–Reference Dinour, Bergen and Yeh27).

Conclusions

The results of the present study revealed an increase in the self-reported consumption of high-density, energy-rich foods such as sugar, processed foods and soft drinks. Although this pattern of change is similar to the trends observed for the overall Brazilian population, indicating the need to improve access to healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables, the greater increase observed among those families with a greater dependence on the CCT suggests that the programme must incorporate actions to facilitate healthy eating. Public policies should emphasise the availability of healthy foods to promote healthy eating habits.

Food choice decisions are not solely based on economic rationality and health. Families face dilemmas including the wide availability of affordable, energy-dense foods of low nutritional value, the dissemination of advertisements for these foods, and the symbolic value of the available foods and their value effects. All of these aspects should be considered in the context of public policies to promote healthy eating. The implemented actions should affect multiple factors that influence the various dimensions of eating practices, including the family, the community, the media, institutions (schools, health systems), meal providers, and the broader process of building social values.

Acknowledgements

The Brazilian Institute of Social and Economic Analysis (IBASE) developed and provided overall coordination with support from the National Funding of Studies and Projects (FINEP). There have not been any prior or duplicate publications or submissions for publication. No conflicts of interest are declared. J.d.B.L. participated in the manuscript concept, statistical analysis and manuscript writing and revising. R.S. participated in the statistical analysis and manuscript writing and revising. L.B. participated in the overall study concept and design of the study, supervising data collection and manuscript writing and revising. R.S.-C. participated in the concept and design of the study, supervising data collection and manuscript writing and revising.